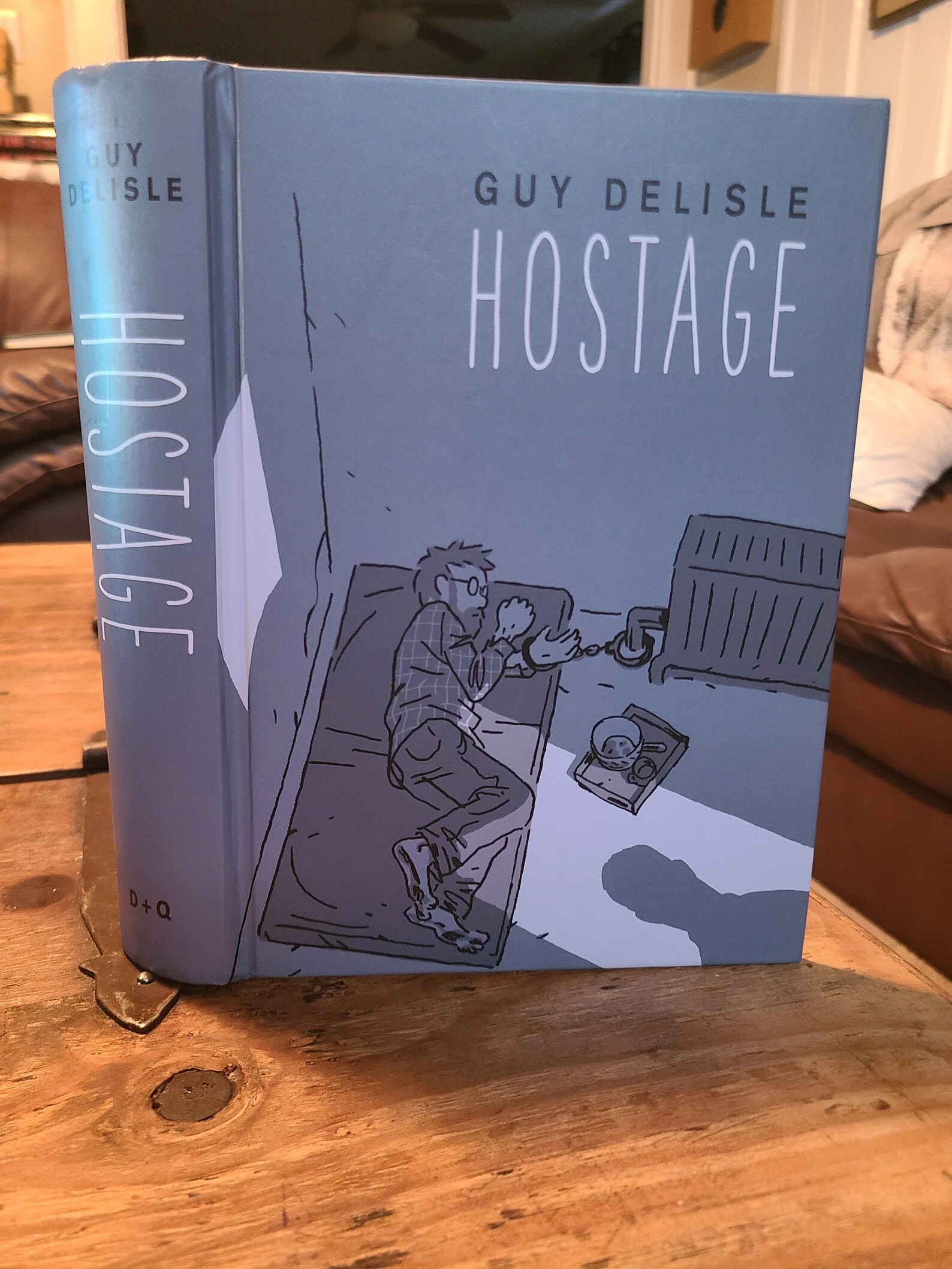

But Hostage is a comic, and it's Delisle's art - his character design, his use of page and panel layout to underscore the mind-numbing sameness of solitary confinement while controlling the story's mood and pacing - that makes us feel André's plight so deeply.

The account of André's experience, dictated to Delisle years later by the man himself, would be powerful enough, if depicted in prose alone. Mono-toe-ny: A page from Guy Delisle's Hostage. To keep his sanity, he literally counts the passing days (at one point the notion that he's temporarily lost track of which day of the week it is induces a panic attack) and challenges himself to recall details of French military history. Any deviation from this crushing routine - the sound of distant gunfire, a new voice in the hallway, or having his photograph taken by his captors - inflames André's imagination with thoughts of rescue, or sends him spiraling into despair. His days pass with metronomic regularity: fitful sleep broken up by the "click, clack" of the door, which augurs a meal of thin vegetable soup, or a bathroom break. We watch them storm into the room where André is sleeping, forcibly abduct the bewildered and terrified man, and shove him into the backseat of a car.įor days that stretch into weeks, and weeks into months, André's existence shrinks to one of numbing monotony, as he is kept - mostly - in a small darkened room, handcuffed to a radiator beside a bare mattress.

That same, muted grayscale color-scheme will stay with us throughout the book, because the man imparting those words - Christophe André, a Doctors Without Borders administrator assigned to the Caucasus region in 1997 - will spend the bulk of Hostage's 432 pages in darkness.īut first, we see a car pull up to the building, and several dark shapes clamber out.

Your purchase helps support NPR programming. Close overlay Buy Featured Book Title Hostage Author Guy Delisle and Helge Dascher

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)